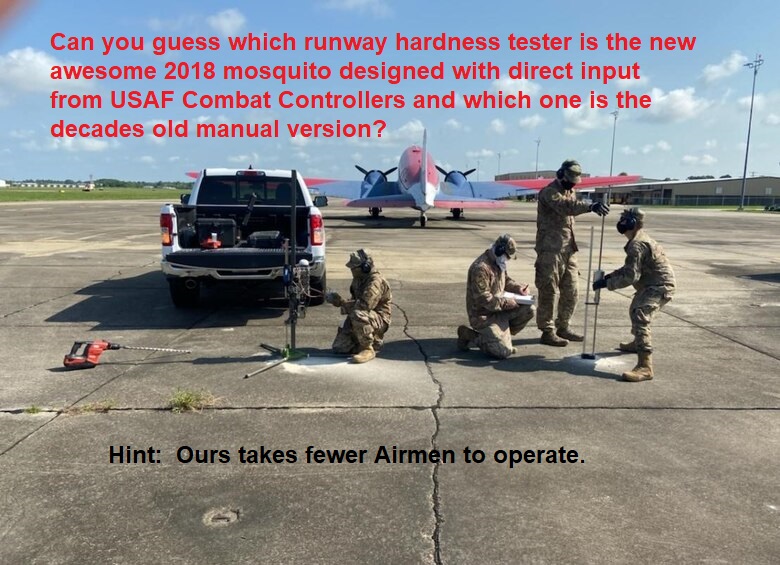

Mosquito:

A portable Runway Hardness Tester for USAF Special Ops that weighs 30 pounds and fits in a rucksack.

Through the

Air Force Research Laboratory ,

the

Combat Controllers

at

Hurlburt Field

wanted an automated version of a manual cone penetrometer used for decades in their role of supporting air operations from the ground. Their current method was simple above all else, but required 2 or 3 airmen to operate.

2007: I was the main project engineer and designed everything mechanical you see here with the exception of the folding legs. It came back once for an electronics upgrade, and that's when they started asking "How do we buy more of these?" There were a couple more small iterations, then they took it to Afghanistan. It came back covered in dirt so I know they used it for real. This was the first of its kind productized version but really it was a prototype with almost no testing. They did our testing for us.

It wasn't perfect the first time and required a little TLC but the fact that they brought Mosquito into an active war zone and used it to decide where to land planes is why I call it a huge success. They must have asked us for more of these about 10 times.

When I joined the project, Alliance Spacesystems had completed phase one of the SBIR with a working prototype. My job in phase two was to design a refined version that met several goals, the hardest being the ability to collapse into a rucksack that might dangle below a descending parachuter. We had a mass limit and

MIL-810

requirements at the extremes of temperature, dirt and moisture. Our team was also asked to automate the pencil and paper data collection to output to a "grab and go" USB flash drive.

In operation our design needed to be about six feet tall and make measurements accurate to about a millimeter. The requirement to collapse into pieces made this difficult. I could not use a

magnetorestrictive sensor

or either kind of strip encoder. We looked at optical laser mouse sensors but they are susceptible to dust, water and mud. Every string potentiometer that was light enough was also so flimsy the airmen assured us they would snap the thin steel cable. We tested an ultrasonic sonar device that was almost perfect but would occasionally flub a reading when we were pouring water over it. The method we settled on crossed from one segment to the next with ease, and worked even when we packed handfuls of mud on it.

It was a privilege and a thrill to meet and work with the actual Operators at Hurlburt field who did this stuff for real. You can not get that kind of design guidance on paper. Some of them were active (and often "not here today") and others now serve quite effectively in more of a research project manager role.